Going into the 2019 World Cup final, Kumar Dharmasena was the best umpire in cricket if you believed in ICC awards. Some 9 hours later, he was the reason why New Zealand lost the World Cup “by the barest of margins” and was globally castigated by most of the cricketing world. Because of a decision that gave England 6 runs instead of 5 and kept its best batter on strike, the final was tied, and later won by England in even more dramatical circumstances. Forty five days and forty eight games to decide the champion, only to end in technicality and a wrong umpiring decision.

Or is it? Was Kumar Dharmasena the actual reason why New Zealand didn’t win the World Cup?

****

Think about a victory – a victory of some player or team you support. How do you feel now? Happy? Relieved? Proud?

Now think about a defeat. Think about a horrible, agonizingly close defeat. It hurts, doesn’t it?

When reminiscing a major tournament win, we don’t actually feel happiness. We mostly recollect how happy we were that day. But a big game defeat? Heck, a big game defeat that went very close? That eats you up from the inside.

We move on from wins but almost never move on from a soul shattering loss. We think more about failures than success. Which is why it is vital to think about it in the right way.

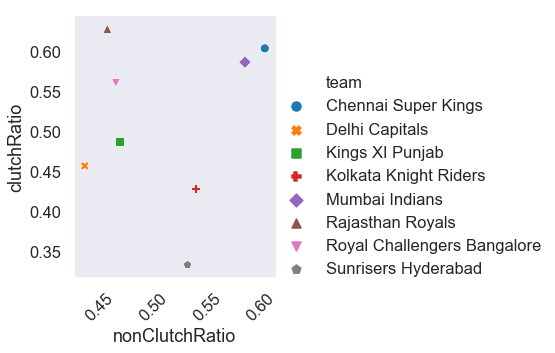

Because trying to discuss psychology without data is just philosophy, let us look at the ratio in which teams win close IPL games. The criteria for a game to be called a clutch game is fairly simple: the games must be won with a margin of 5 runs or below or the balls remaining in a successful chase should be 4 or below. This is to weed out games where teams need 1 run or 2 runs going into the final over. They are more advertiser friendly games than clutch games.

| Team | Close Games win % | Non Close Games win % |

|---|---|---|

| Chennai Super Kings | 0.604167 | 0.603604 |

| Delhi Capitals | 0.457143 | 0.436090 |

| Kings XI Punjab | 0.487805 | 0.468750 |

| Kolkata Knight Riders | 0.428571 | 0.539062 |

| Mumbai Indians | 0.586957 | 0.585185 |

| Rajasthan Royals | 0.628571 | 0.457143 |

| Royal Challengers Bangalore | 0.560976 | 0.465116 |

| Sunrisers Hyderabad | 0.333334 | 0.531746 |

Now, let me be very clear before going ahead. This data is absolutely not useful for predicting things. It has cool observations and that’s just it. There is only one thing I want to take from this data. It is that teams the 4 teams with the lowest non clutch game ratio (DC, KXIP, RCB and RR) have a higher clutch game win percentage than non clutch game win percentage.

So what does this mean for us?

Inferior teams have an advantage when the game is evened out. The advantages? Nervous opponents, yes. I would be foolish to say that nerves don’t exist. But there are other factors that go with it. The most important of them all is fortune.

To make a discussion about clutch games, we need to speak about luck. But luck is just luck. Plain luck. There’s no way to quantify or predict luck.

Think 2 teams A and B. Team A has superstar players, elite technical team and a very good budget that helps the team run. Team B is a team which we could call it as a mid table side. For team A to play a “close game” against team B, they’d have to under perform to an extent to make the game close. Once the game is close, luck carries a good amount of weight in deciding an outcome.

Skill or performance largely decides the outcome of a game because a game is played in the longer run. There is an element of luck of course but in skill based activities like sports, performance is the deciding factor in the longer run. So when the game is even and thinned out to its final over or two, the space isn’t sufficient enough for skill to exert dominance over luck and this is where luck takes over and carries more weight, giving inferior teams an advantage.

Inside edges to the boundary or stumps, a perfectly timed shot finding a fielder, a ball that wasn’t a part of a plan getting a wicket are all different variants of luck. Players have to take risks in the final overs. These risks amplify the luck factor involved.

De Villiers failed in the 2016 IPL final because he came in where he had to take risks. He wasn’t lucky enough to pull it successfully. Kohli failed in the 2019 WC semi final because in adverse conditions you need to have some good fortune. He didn’t. It doesn’t say anything about Kohli’s ability to play in knockouts or De Villiers in close games. World class players have consistent performances over a period of time. That’s it. To reach their level, they overcame and trumped the best of the best. Trying to make a judgement about them by looking at clutch games or situations is not just not right. It is unfair to the players.

It isn’t just nerves. Players are nervous in their first trial as a kid, they are nervous when a selector comes to see them, they are nervous in their debut match, in the time they take to secure a place for them in a team. I’d go on to say a player is under more pressure when he dots up 4 consecutive balls, batting first in the 18th over of a silly bilateral T20 more than when he/she walks in needing 20 to win in 2 overs in a knockout.

The thing is this. Pressure exists. But pressure exists in many situations. Not just in close or title clinching games. An international player has to overcome pressure at different points to be successful. Them failing in a game isn’t just due to pressure. There are other factors involved.

Now coming back to clutch games, there’s almost always a key point that just makes a team or a player win. These points are oftentimes at places where fortune carries more weight. The Ben Stokes – Guptill overthrow (sort of) or let us even take another game that happened that same day in that same city, the 2019 Wimbledon final where Novak saved 2 championship points, Nathan Lyon missing a simple run out in last year’s Headingley test are all such points.

But are they?

There’s a problem with attributing an entire game to a single key point. It is a reductive move that focuses on places where luck has a strong influence. So we’re not making points about performance. We’re not analysing a game to its fullest.

Let me explain.

Take the 2019 CWC final. The amount of abuse Dharmasena got and is still receiving is unfair for a reason. It was a situation never seen before. Like, what are the odds of that happening? Dharmasena swallowed the whistle without making a call that’d probably have changed the game.

Dharmasena’s decision is an element of luck. Sure he should have done better. But his failure takes everything away from the conservative batting performance that New Zealand put that day. Was it the residues of the 15′ final where they were bowled out trying to be aggressive, I don’t know. But you don’t win too many ODI games these days scoring 241, no matter how the pitch is with 2 new balls. New Zealand’s batting lineup never pressed the accelerator at any point of the game.

In short, they didn’t control every element they could’ve controlled. A team fully deserves to win only if the control whatever they can. Once you don’t control, you leave a lot to chance and chance being chance will flow in any direction. It flowed in England’s direction that side. Dharmasena’s was just a single mistake in front of the overall 50 overs of New Zealand being pushed hard by the English bowlers.

It is easy to suggest that Roger Federer has a mental weakness after conceding 2 championship points. But that was due to a loss aversive Djokovic taking more risks combined with his insane ability and the risks paying off. Federer being the great champion that he is came back that very final set to secure a break point which Novak saved. He was still in that game but by that time, you could see Federer show fatigue.

Fatigue is another factor that determines games that go deep and long. A 38 year old Federer will always be behind a 32 year old Novak in terms of fitness in the final set. So, when speaking about the moments that changed the game, it is imperative to discuss Roger’s performance in the 2 tie breaks he lost along with the last set. If we just look at the last set, Federer will look like a choker which a 20 time Grand Slam winner clearly isn’t. It’s unfair on him.

So if analysing parts of game where skill doesn’t play a major factor, why do we keep speaking about it? Turns out, it is a combination of recency bias and simulation heuristic.

We as humans, give unwarranted weight to what happened recently. And when trying to undo a defeat, we tend to look at just few incidents. These incidents are exaggerated like rain drops in front of a light beam. Our mind is intrinsically lazy. So it more often than not, tends to undo the most recent incidents – the Dharmasena decision or the Nathan Lyon runout or Jadeja failing to take India home in Hyderabad 09′. It is like a switch. A “what if” switch. Turn on and Nathan Lyon completes the run out and Australia have an overseas Ashes win.

To this date, we don’t blame the Indian bowlers who conceded 350 runs that day. We don’t blame the Australian batsman who failed to score in that Headingley test. Australia were purely in it because of the bowlers. The mind has to travel a long distance to undo and think about the Indian bowlers conceding lesser runs or Australian batsman scoring more. It takes energy. It is very difficult to think about the other possible outcomes. But we have to think.

Whatever opportunity that slipped away from our hands could’ve been made just that little bit bigger with better grip to hold on. Thinking about the last incident that made someone breakup with his partner is futile because that incident alone was not culpable. Thinking about the way the person behaved to his partner overall will give a better picture. It gives a chance to correct that person instead of whining and thinking what if. It applies for sports teams and fans too.

Teams must try to have a definite advantage in skill and performance instead of leaving things to chance. And us fans must factor in all possible elements before making a judgement and attributing a defeat to a player. It doesn’t make for a better story. It makes for better analysis and that should be our focus.

Leave a Comment